Persimmons

What can persimmons teach us about process, presence and pleasure?

This month in Pacentro the forest is saturated by deep hues of burgundy, orange and yellow. The early sunset even makes the mountains blush.

As the leaves of the Diospyros kaki undress they reveal plump orange fruits.

For three years now, I wait until this precise moment to collect unripe fruits from trees that I know around the mountain. I then slowly dry them using a traditional Japanese technology called, hoshigaki.

This method of preserving is an embodied practice that invites me to be in intimate relationship. No rushing to consume the fruit’s ripe flesh, a reminder to be in touch.

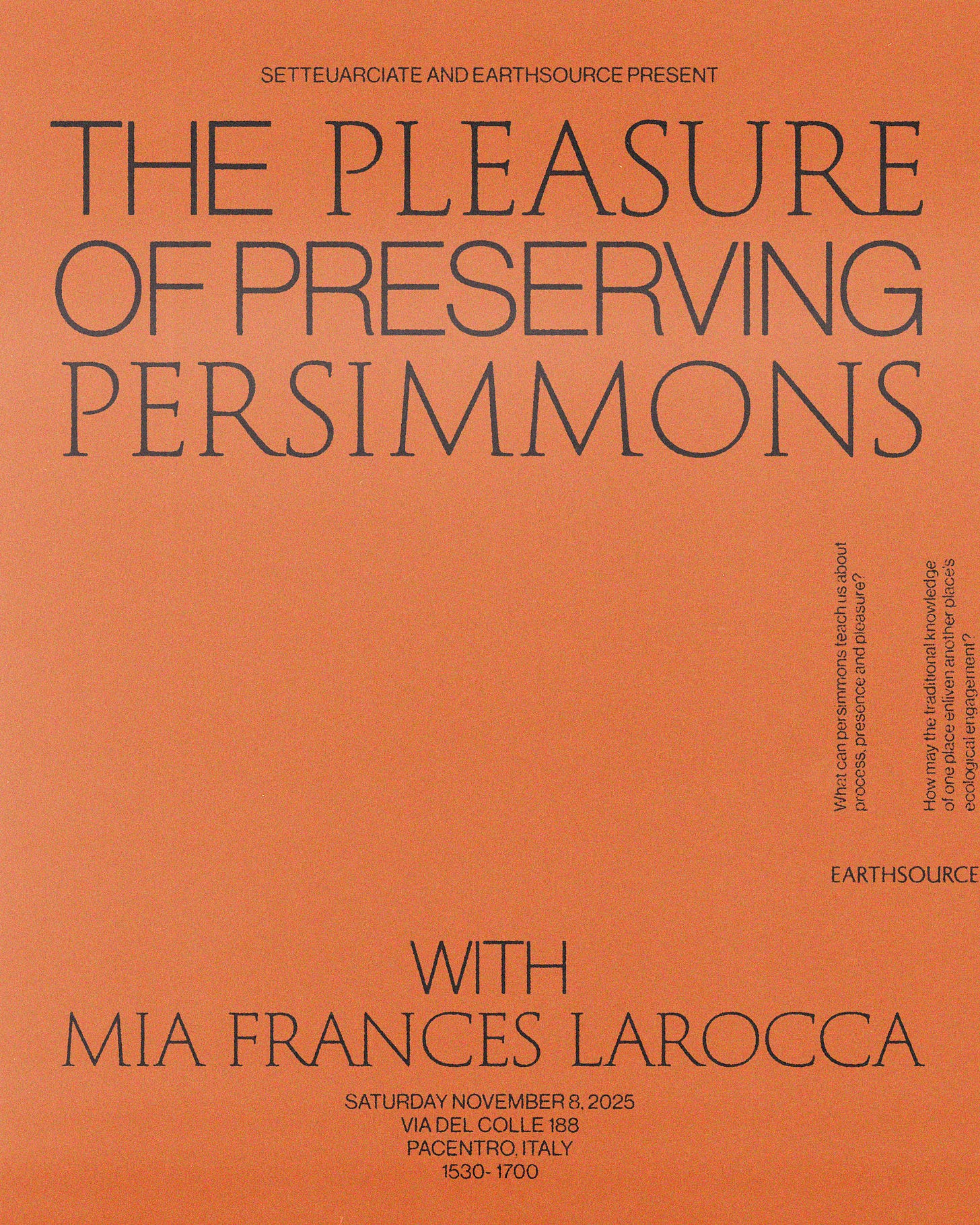

At the beginning of November, the Earthsource team visited the setteuarciate studio and we co-hosted our first event exploring the pleasure of preserving persimmons together.

Each year the scale of my hoshigaki project grows.

It began with me in my kitchen as I delicately massaged less than twenty fruits just out of curiosity. Delighted that it worked, the next year it grew to processing baskets full of fruit with a friend. He loved the taste of my first experiment and was invested in ensuring there would be more.

After the second year, I became kind of persimmon famous in Pacentro. People that tasted my hoshigaki would stop to remind me the countdown until fall when the next batch would be ready.

I was obsessed with this affection because I was exclusively using an overlooked fruit in Pacentro. I felt like I was contributing to the expansion of what a persimmon is or can be.

When my head hits the pillow at night my dreams are often filled with questions like — how can I build a beautiful hoshigaki system like those I see images of in Japan?

This year my dreams came true.

Paola and Fergal introduced me to the persimmon tree on their terrace. The tree is great, but what is even more impressive is that it grows in front of the most perfect shed for drying. This year, the hoshigaki project became a large scale installation.

I am not sure if Paola understood how tenacious I am when chasing a desire the day that I asked her if I could use her shed for a month. But thanks to her, we are now drying hundreds of persimmons.

I visit the strings of orange pearls and she swears to me it is the happiest the shed has ever been.

To dry hoshigaki outdoors you need to have cold, dry mountain air and sunlight during the day. The shed is exposed to the morning sun and covered by a roof. Temperatures are optimal between 5–15°C with a low humidity.

From what I understand, the heaviest hoshigaki activity is in the Nagano Prefecture in Japan. I have yet to visit Japan but I have a hunch that Pacentro in the fall feels exactly like fall in the mountains of Nagano.

For me, the only difference between the two rural mountain ranges is that I am desperately trying to bring some semblance of onsen culture to Pacentro. But that is an idea to develop next year.

The whole process takes anywhere from 2 - 4 weeks and requires daily massaging after a soft leather forms during the first week of air drying. That means that since November 8, I walk to the shed to massage the persimmons every day if not every other.

As I dry-preserve persimmons, I am able to express love via touch.

So many Italians complain that cachi season is short and inundated. One can only eat so many fresh fruits. Thanks to the human ingenuity embedded in hoshigaki, our palate enjoys delicious possibilities that can only be unlocked by playing with time. The daily massages prolong the persimmons’ presence well into next April or May.

The persimmon tree was brought to Italy in the 1800s. The first ‘official’ record of the tree rooting into the ground here is in 1871 in the Boboli gardens. I’m sure the plant existed in someone’s collection somewhere before this date but for all in tensive purposes we will refer to the late 1800s as the moment when i cachi entered the Italian landscape.

There is however a missing link after the migration of these species. The tree lends itself to place but cultural knowledge did not accompany this ecological exchange. I see potential for more relationships if I create a space for people to dry persimmons together.

When working with hoshigaki, we often begin distinguishing between Fuyu and Hachiya varieties. Persimmons are the ideal fruit to teach someone about tannins. If you have ever bit into one too early, your tongue and you know just what I mean.

The Hachiya variety has more tannins and therefore lends itself better to the process of hoshigaki. In Italy there are over 20 recognized varieties of persimmons — the variety is thanks to hybridizing and grafting. The two most popular varieties you hear Italians mention by name are il caco Vaniglia and il caco mela. Il caco mela is not astringent like the Fuyu; whereas, il caco vanglia is astringent like the Hachiya cultivar.

Astringency is important for hoshigaki if you are aiming for a sugar bloom. But to be honest, I have worked with fruit from abandoned trees so there is no one to tell me anything about the tree other than my observations. Hoshigaki works if you peel unripe fruit and follow daily massages.

Persimmons trees are botanically quite special because they can be planted by seed or replicated through grafting. They can be either monoecious or dioecious meaning that some trees have male and female flowers while other trees have only male flowers and need a complimentary female tree nearby for pollination.

The persimmon tree is friend to many pollinators because it offers both nectar and pollen. The flower is open and generous making it an accessible choice for native pollinators with larger bodies like a Violet Carpenter Bee, Xylocopa violacea.

The flowers emerge in May and after pollination it takes the fruit almost seven months to mature. Not all persimmon fruits have seeds because the tree falls into the interesting category of parthenocarpy. Parthenocarpy is an adaptive strategy that allows a tree to set fruit without pollination. Seed or no seed, it should not influence your hoshigaki project too much. A seed discovery gives you more information about the relationships between pollinators and trees in your ecosystem.

We gathered under the persimmon tree to ask questions about the ecosystem in Pacentro, letting hoshigaki guide us in our inquiry. Of course we leave a lot on the tree for non-human species. Birds and insects love eating the persimmons just as much as us.

A silent peace washed over us as we rhythmically peeled persimmons with the sound of water falling in the valley. A few people broke silence to acknowledge how meditative the process became — picking, peeling and stringing.

Whether or not you are flirting with the idea of trying hoshigaki this year, I will leave you with this recipe for my favorite persimmon pudding.

I served this persimmon pudding during an event hosted by Io Non Ho Paura del Lupo and Rewilding Apennines in 2023. My idea was to feed 200+ people using only fruits that I collected from abandoned land in and around Pacentro.

It is a love language for me to respond to annual messages from so many friends asking me for the recipe I follow. I am charmed when I realize that just maybe people associate me with the persimmon tree.

Thank you to Valentina Amarl, Mal Tayag and Sky LaHood of Earthsource - also a special thank you to Paola and Fergal for allowing my crazy persimmon dream to come true — cheers to many more!

Join us in 2026 for more hoshigaki events in Pacentro.

Really really loved this. What important and beautiful work!!

Persimmons are such an unexpected fall treat!