In keeping up with a spring harvest for weaving materials, it is now time to shift my attention to olive trees. Pruning polloni away from olive trees is a big focus during spring.

Polloni are the “suckers” that grow at the base of an olive tree. They are unwanted because they take a lot of energy away from the established plant, as implied in their name — suckers.

Those olive branches are the building blocks for a lot of woven pieces that I can keep my hands idle with next winter. The time to harvest is now so the wood of the new shoots does not become too stiff to work with. I am asking all my friends with olive groves if I can help them prune so I can walk away with arms full of polloni.

The first time I came to Pacentro on my own was March 2019, classes were on Easter holiday and I needed to write a paper for an Ethnobotany course. My two friends, Niccolò and Diana, were to write with me and so we took advantage of an empty home in Pacentro knowing we would arrive just in time for olive pruning.

We never would end up writing a paper on olive pruning.

Our first night in town I ran into a friend and she asked me if I had been to “the old house.” I said, “which one, aren’t they all old here?”

She laughed and told me about the new cheesemakers, Alla Casa Vecchia, just a up the street from me and suggested we pop our heads in if we were interested.

We did just that and the rest is history.

Niccolò, Diana and I spent a few days listening to Giocondo, Stella and Virginia tell us about their version of Pacentro. They so generously shared meals with us and let us ask about cheesemaking and transhumance in the Majella. Before our departure to Bra, I knew I had to ask if I could do a cheesemaking stage with them in the late summer whilst I wrote my thesis.

They said yes and that decision determined my future in Pacentro.

Each spring when I would go down to milk the goats with the shepherd, Giocondo. We would take a small break at the end of the milking session to see who could pick the most wild asparagus. Those early mornings of March and April, when I stayed back to make cheese, we would always wait to see a tender bouquet of wild asparagus enter the front door in Giocondo’s gigantic fist.

Once the first bouquet of wild asparagus is spotted, people are bewitched.

Curious beginners will ask for tips as to where or how to find the plants — you will see bodies bent over, sticking out of the olive groves as people pilfer through green grass.

There is a little colony of Danish philosophers that make an annual appearance in Pacentro. I specifically met two of them, Mille and Kaare, while I was making cheese one day. We spoke about beekeeping and grazing — I mentioned that the landscape was impaled by wild asparagus at the moment.

They were quick to tell me that philosophers are mad for wild asparagus and that they must learn how to find the plant.

I taught them how to find the plant and they wrote me saying how happy they were.

I however am still waiting for a philosopher to tell me why they have such an affinity for the spears.

Until then, I will offer my own reflections.

Each time I go out in search of wild asparagus in Abruzzo I notice the mother plant often nestles in a nice little agroforestry system in the understory of the olive trees. It made me question if this relationship was symbiotic or parasitic.

It feels frivolous to speculate on the relationship between olive trees and wild asparagus.

It is something negotiated deep in the soil.

I believe humans also experience particular relationships that nourish us in ways that can’t be explained to others. It’s better that way. Just feel it and enjoy the tenderness that shoots up from the embrace of that exchange.

Relationships of this nature help us grow.

I am lately most fascinated by plant’s strategies for life.

Asparagus, both wild and cultivated, is perennial. Olive trees are perennials as well.

The difference between annuals and perennials lies within those strategies for life. Perennials have attributes that lend themselves to long term survival; whereas, annuals have quick lifecycles still aimed at long term survival but in a quicker manner.

If I had to make a quick judgment about annuals and perennials in relationship to honey bees, I would say that honey bees almost exclusively have more relationships with annuals. Honeybee pollination is often crucial for annuals to complete their cycle from flower to fruit and then to seed. Perennials have more complex or nuanced relationships with pollinators as they rely on pollination through wind, water, animals or self-pollination.

The breadth of the wild asparagus plant reminds me of artichokes. Like artichokes there is this sweet lineage of the “mother” and then the tender edible parts are what we are seeking. I remember visiting a farmer growing Castellammare artichokes near Pompeii — he was the first to explain to me this familial growth. In Campania, the mother artichokes are covered with a terracotta hat to keep them tender and then four or five children begin to bloom around her.

Recently a friend told me if I was a vegetable I would be an artichoke. I would have to agree.

I find it sweet that the mother plant of wild asparagus, like the thistle family, itself is quite protective. She is intimidating— a fern equipped with many spines that will grab you if you are not careful. You need to take time to appreciate how to handle her.

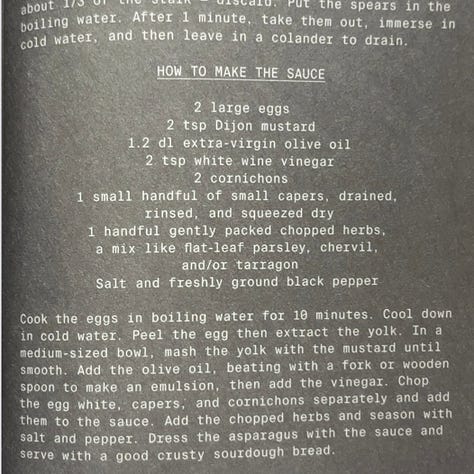

One of my most coveted cookbooks, all the stuff we cooked, by Fredrik Bille Brahe from Café Atelier September, has a recipe for the Apollo style sauce gribiche to dress asparagus. This is a simple recipe to add to your spring rotation.

If we want to learn when to look for wild asparagus. We can look for signs from our environment, cultural signs in Pacentro are the pile of olive branches that begin to litter the groves.

I find looking for wild asparagus to be incredibly mindful.

You first learn to identify the mother plant then you have to gently look around her spikes to see tender shoots pushing up from the earth. Sometimes the spears are unbelievably long and right in front of you - it is easy to overlook them. Once you learn some of the plant’s behaviors it becomes easier. I find I must always tread lightly and watch where I step because they could be right at my feet.

To harvest wild asparagus you want the shoot to be nice and tender. You can run your fingers along the spear and feel where the stalk starts to harden. Pinch just above this hard spot to leave behind the woody end. If the stalk feels woody throughout you should leave it be.

Please review the honorable harvest before collecting anything.

** This piece is in no way encouraging or instructing readers to eat things found uncultivated or cultivated that you do not know to be edible.**

Mia, I can't wait to meet you. I'm enjoying your writing very much. I just started a Substack about our journey to Pacentro (where we just bought a little house) and I hope when I return (probably late Octoberish) we will have a chance to eat something together!

The disclaimer at the end lol! Fascinating read all stuff I did not know